As part of the FIND project, partners visited the Tricastin Nuclear Power Plant during the replacement operations of a large-sized siphon (approximately 6 meter high). This visit helped the team understand how to apply new inspection techniques in areas that are very difficult to access.

What is the siphon and why does it matter?

The siphon is part of the nuclear power plant’s low-pressure preheater, a system that helps improve the plant’s overall energy efficiency. In a nuclear power plant, water is heated to produce steam, which spins a turbine to generate electricity. Making the most of the heat available in this steam cycle is therefore essential.

This is where the low-pressure preheater plays an important role. Here’s how, in simple terms:

After passing through the turbine to create electricity, the steam is cooled back into water in the condenser. At this point, the water is very cold. Before it returns to the steam generator to be heated again, it goes through a preheating step. To preheat the water, a small portion of steam is taken from the system before it reaches the turbine. The siphon is connected to the heat exchanger carrying out the preheating step and collects condensed water, which is then fed back into the cycle.

This preheating process enhances the overall thermal efficiency of the system and also helps to minimize the thermal stress that occurs when the feedwater is introduced back into the steam cycle. The amount of steam extracted and thus not used to drive the turbine must be carefully optimized to obtain maximum power plant thermal efficiency.

But why cooling the water so much if it’s going to be reheated right after? The answer lies in how power plants make electricity. Because of the Carnot theorem, power plants work best when there’s a big temperature difference between the “hot side” (steam from the reactor) and the “cold side” (water leaving the condenser). The turbine produces the most energy when hot steam enters and exits into a very cold environment. That’s why the condenser cools the steam as much as possible: the colder it is, the more efficiently the turbine can extract energy.

Sending this very cold water straight back to the steam generator would make the next heating step much harder. This is why the low-pressure preheater warms the water slightly. By using a little steam to gently warm the water returning from the condenser, the plant reduces energy losses and helps the whole system operate more efficiently.

Why inspecting the siphon Is difficult, and how FIND is addressing this challenge.

While the siphon is essential, inspecting it is far from simple. It is enclosed inside a concrete structure, making it largely inaccessible. Only a very small opening at the bottom and the top part above the concrete are reachable. Because of this, conventional Non-Destructive Examinationmethods to measure how much wall thickness remains cannot be applied. Without direct information about the real damaging of the component, EDF must replace it preventively to ensure safety. Extracting the siphon requires cutting it in half, making it impossible to reinstall, even if, after removal, it proves to be still fit for service.

This is where FIND comes in. To overcome these limits, KTU, one of FIND partners, is developing a guided wave inspection technique. This approach aims to screen the component completely for wall thickness loss using only the accessible top part. If successful, this technique could detect any thinning of the siphon’s walls without needing full physical access.

This research is essential. The siphons material, diameter and wall thickness are representative of many balance-of-plant components, which are located outside the primary loop and thus not subject to the same strict inspection requirements.

“Having an inspection technique based on guided waves would allow us to assess corrosion of components with limited accessibility, improving safety and avoiding unnecessary preventive replacements” says Andreas Schumm, engineer at EDF.

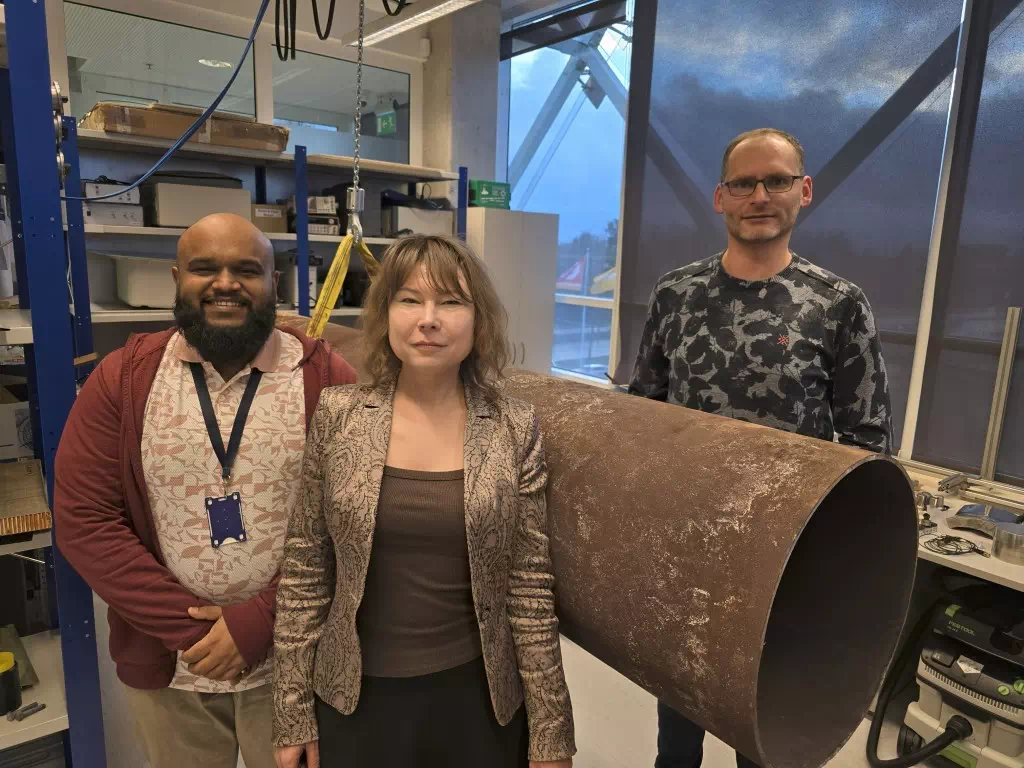

The replacement of the siphon in Tricastin was an important milestone for the FIND project as EDF and the Tricastin Nuclear Power Plant were able to ship the retired siphon (after more than 40 years of service) to the Prof. K. Baršauskas Ultrasound Research Institute of Kaunas University of Technology (KTU). The component, cut in half to allow its extraction, is now providing KTU researchers with a rare opportunity to examine how factors such as surface condition, welds and geometry influence the propagation of guided waves.

Access to a real, previously operated siphon is invaluable: it allows the KTU team to validate their inspection approach under authentic industrial conditions and to refine methods that could eventually support Structural Health Monitoring systems tailored to the constraints of nuclear facilities. This research is especially relevant for large balance-of-plant components like the siphon, which are currently impossible to inspect directly due to limited accessibility.

Learn more about ultrasonic guided-waves with this presentation : PowerPoint Presentation